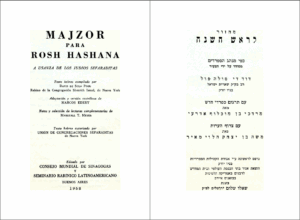

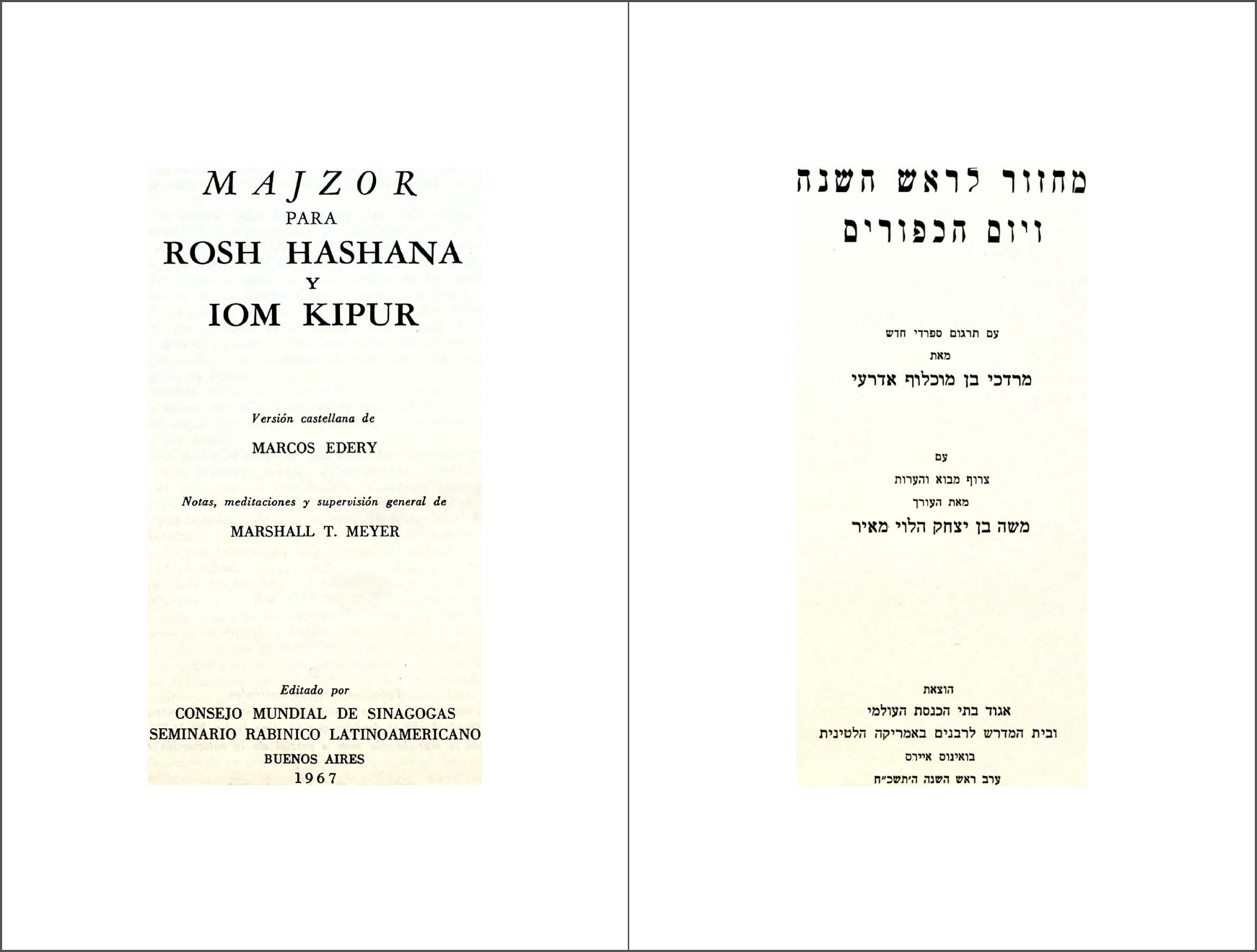

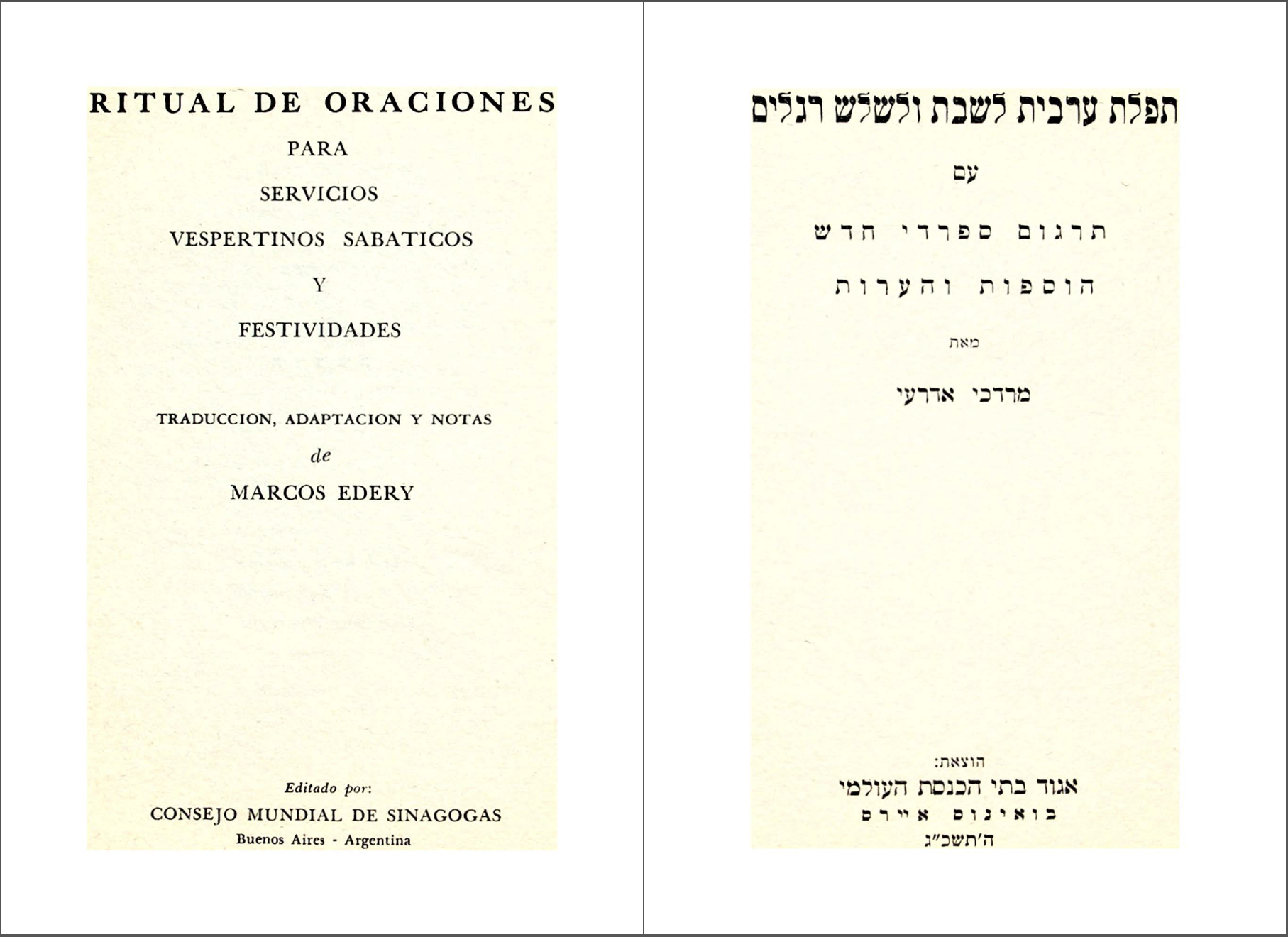

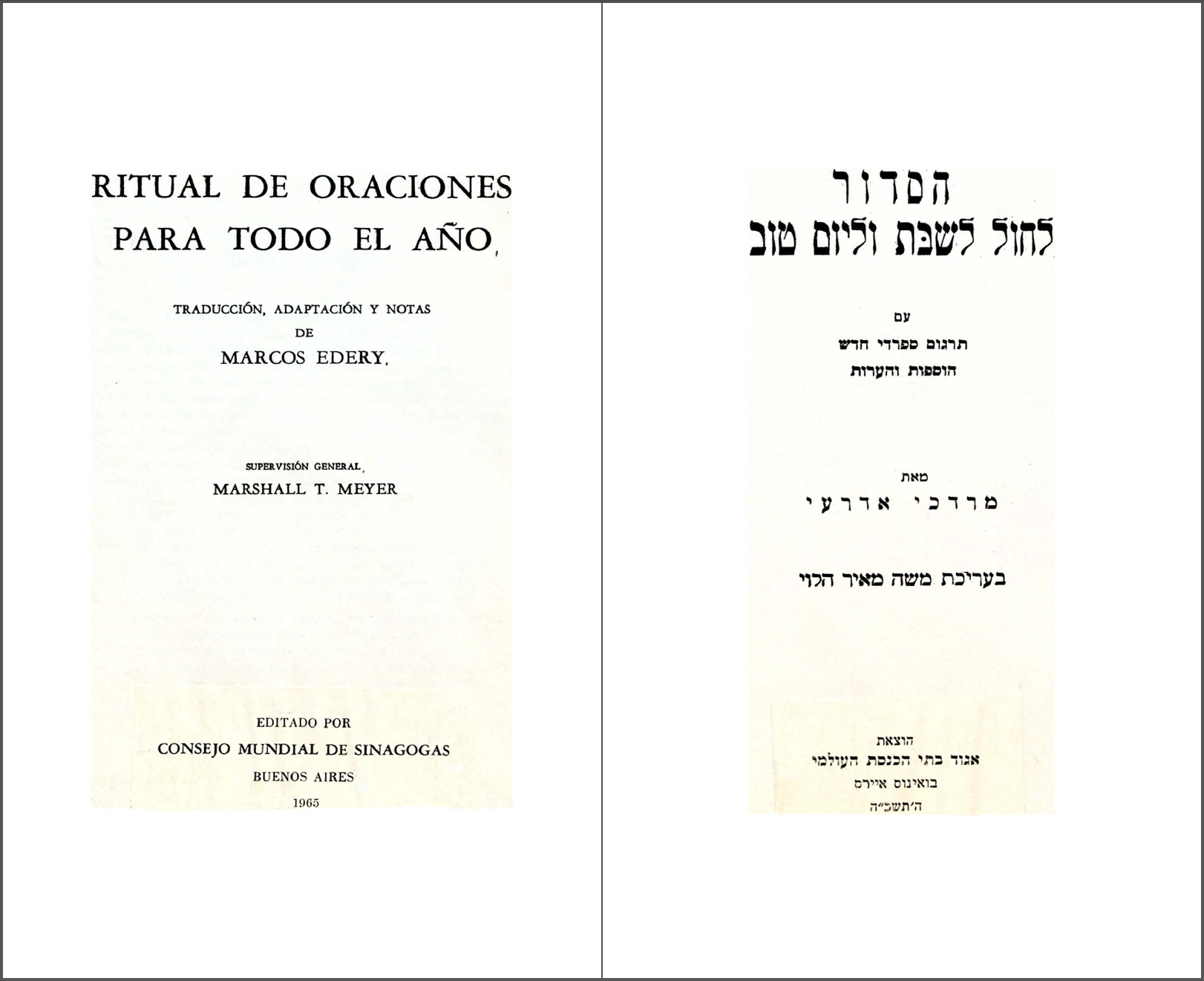

מחזור לראש השנה Majzor para Rosh haShanah (1968) is a bilingual Hebrew-Spanish prayerbook for Rosh haShanah compiled and translated by Rabbi Marcos Edery z”l, and published by the World Council of [Conservative/Masorti] Synagogues under the supervision of Rabbi Marshall T. Meyer (1930-1993). Earlier prayerbooks represented the Ashkenazi liturgical tradition. This is the first siddur that we are aware of for Sepharadi congreations in the Conservative movement. The Hebrew is based primarily on the S&P siddurim compiled and translated by Rabbi Dr. Savid de Sola Pool. Besides the liturgy (in the Ashkenazi nusaḥ), the prayerbook is prefaced by Seliḥot and includes essays concerning prayer by 20th century scholars in Spanish translation.

This work is in the Public Domain in the United States by treaty according the Uruguay Round Agreements Act (1994), 50 years having passed since its publication in Argentina (the general term of copyright for works published between 1957 and 1997).

Source (Translation) Translation (English)

Buenos Aires, Tamuz 5728

Julio 1968

Buenos Aires, Tamuz 5728

July 1968

“📖 מַחֲזוֹר לְרֹאשׁ הַשָּׁנָה (מנהג הספרדים) | Majzor para Rosh haShanah, a bilingual Hebrew-Spanish maḥzor compiled and translated by Rabbi Marcos Edery (Masorti Olami, 1968)” is shared through the Open Siddur Project with a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International copyleft license.

![Maḥzor haShalem l-Rosh haShanah - Nusaḥ "Sfard" [Ḥassidic] (Paltiel Birnbaum 1958) - title page](https://opensiddur.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/title-birnbaum-rh-sefard-mahzor-1958.png)

Leave a Reply